RAF Drem was responsible for the defence of the City of Edinburgh and the shipping that operated through the Firth of Forth Estuary.

In the early stages of the war, Spitfires from RAF Drem fired the opening shots of the air war over Britain as the Luftwaffe probed the Firth of Forth in a weather reconnaissance. Drem was also the home of the famed Drem Lighting System: a series of lights set up to be visible only to pilots in the landing pattern that overcame the visibility issues of the Supermarine Spitfire when on approach. It saw a marked upturn in success rates and pilot confidence while night landing and was rolled out to almost all RAF airfields.

By mid-1942, RAF Drem was considered a second-line station. The Battle of Britain had been fought and won; Fighter Command was on the offensive, and RAF Drem was now a place where squadrons would be withdrawn for rest. It was where 453 Squadron would start its story. A plucky group of green Australian pilots who would lay the foundation for the squadron's success story. Those founding members who survived the war were affectionately known as “The Drem boys”.

Spitfire Mk.Vb

-

AB792

Squadron codes:

Spitfire Mk.Vb

-

AD298

Squadron codes:

Spitfire Mk.Vb

-

AD386

Squadron codes:

Spitfire Mk.Vb

-

AR362

Squadron codes:

FU-V

Spitfire Mk.Vb

-

BL292

Squadron codes:

FU-P

Spitfire Mk.Vb

-

BL445

Squadron codes:

Spitfire Mk.Vb

-

BL586

Squadron codes:

FU-S

Spitfire Mk.Vb

-

BL593

Squadron codes:

FU-A

Spitfire Mk.Vb

-

BL630

Squadron codes:

Spitfire Mk.Vb

-

BL899

Squadron codes:

FU-W

Spitfire Mk.Vb

-

BL941

Squadron codes:

Spitfire Mk.Vb

-

BM113

Squadron codes:

Spitfire Mk.Vb

-

BM152

Squadron codes:

FU-Z

Spitfire Mk.Vb

-

BM255

Squadron codes:

FU-T

Spitfire Mk.Vb

-

BM361

Squadron codes:

Spitfire Mk.Vb

-

BM528

Squadron codes:

FU-G

Spitfire Mk.Vb

-

BM572

Squadron codes:

Spitfire Mk.Vb

-

BM631

Squadron codes:

FU-X

Spitfire Mk.Vb

-

BM647

Squadron codes:

Spitfire Mk.Vb

-

EN774

Squadron codes:

Spitfire Mk.Vb

-

EN775

Squadron codes:

Spitfire Mk.Vb

-

EN824

Squadron codes:

FU-U

Spitfire Mk.Vb

-

EN914

Squadron codes:

Spitfire Mk.Vb

-

EN930

Squadron codes:

Spitfire Mk.Vb

-

EN947

Squadron codes:

FU-Y

Spitfire Mk.Vb

-

EN950

Squadron codes:

FU-L, FU-A

Spitfire Mk.Vb

-

EP191

Squadron codes:

FU-A

Authors note: Anyone who has read the 453 Squadron Operational Record Book (ORB) might have noticed some discrepancies in the dates during the first two months of this story. This can be explained by the following note from S/L Morello in the ORB and entries before August, while accurate, may not match the timeline listed alongside them.

“It has been considered that the form adopted in compiling this record is capable of giving a better picture of conditions during the early stage, then would be a diary of events from day to day. It is hoped that it may not be found too discursive and insufficiently chronological. In August and the following months it is proposed to arrange this record in chronological form”

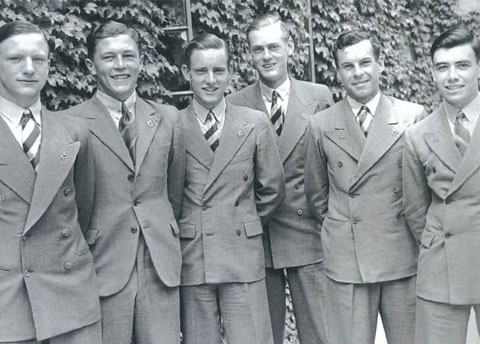

Squadron photo taken during the press day

Standing L-R: Jack Ratten, Tony Morello, Olgierd Sobiecki, Ben Nossiter, Len Hansell, Freddy Thornley, John Barrien, Spit Steele, Wilfred Waldron, Rusty Leith, Dick Ford, Unknown, Tadeusz Jankowski

Spitfire L-R: Jim Furlong, Jack Stansfield, Dick Darcy, Bob Clemesha, Hal Parker, Bill De Cosier, Russ Ewins, Tom Swift

“Good old B Flight” photo taken during the press day

Top L-R: Len Hansell, Unknown

Middle L-R: Unknown, Russ Ewins, Matt De Cosier, Wesley White, Unknown

Bottom L-R: Jack Stansfield, Jim Ferguson (with Dinley the dog), Dick Darcy

"Posted to 453 Squadron, Drem, Couldn't get to 452 as this one is being formed."

- Russ Ewins

The initial forming of 453 Squadron can probably be best described as shaky at best. It wasn’t an organised group of pilots that arrived at an RAF airfield ready to cross the Channel and scrap with the Luftwaffe. It was dribs and drabs of brand new RAAF pilots, fresh out of Operational Training Units (OTUs) slowly arriving at a remote airfield in Scotland.

The first group of the RAAF pilots arrived at RAF Drem on the 11th of June 1942 but not before a few unplanned detours. Freddy Thornley, Gerry Whiteford, Frank McDermott, Russ Ewins and Len Hansell were some of the first pilots to receive their postings to 453 Squadron on June 9th. They had waited out their first operational posting in staff positions at 57 OTU, RAF Harwarden in Wales.

The group departed from Harwarden and spent the night in Chester before boarding a train to the “land of heather, glens and brogue”. The trip had them transferring between different lines and bidding farewell to friends who had received postings to other squadrons along the way.

When they reached Edinburgh, they stopped for a quick bite to eat before heading to the eastern train line that would take them to Drem. While the group immediately picked up on a different atmosphere among the locals in Scotland, they didn't quite realise how strong the Scottish accent could be which resulted in them missing the guard calling out their siding at Drem. When they got off at Dunbar, the next stop, they found themselves with 45 minutes to kill before anything could take them to Drem.

What else would a group of young Australians do in a new country and town but pass their time at “yon wee inn”? ("That small pub" for the Australian audience) The gaggle of new pilots didn’t stand a chance of buying a drink, as the locals, many of whom were ex-RFC (Royal Flying Corps) from the First War, eagerly bought rounds for their new visitors from across the world. Eventually, the group boarded their transfer bus to Drem, with the good mood and banter continuing with the curious local passengers on board.

The warm welcome from the locals was soon overshadowed by the bureaucracy of the RAF. The phrase “shocked but not surprised” feels fitting when the group discovered on arriving at RAF Drem that “As anticipated and in strict accordance with the usual Air Ministry organisation, no one knew anything of our arrival nor of 453 Squadron.”

"No sign of a squadron here yet, No C.O or anything else."

- Russ Ewins

It was common at RAF airfields to have several squadrons based there at once. When the Australians arrived at Drem, they found it also hosting 410 Night Fighter Squadron RCAF and 242 Spitfire Squadron RAF. When the CO of 242 Squadron heard there were pilots floating about with no apparent squadron, he quickly nabbed them to make up numbers in his flights.

The group got their first taste of the Spitfire Mk.V, after months of flying Spitfire Mk.I & IIs at 57 OTU. In the words of Len Hansell and in typical Australian fashion, he reckoned that the Mk.Vs were “a bit of all right”.

The history of 242 Squadron was not lost on the group. They were well aware that they were flying in the legendary Douglas Bader's former squadron, which was still immensely proud of their former leader. Sadly, any sense of awe regarding the presence they were in soon faded. The Australians didn't feel at home in 242 Squadron and were unhappy with how they were being treated as the new spare pilots. It soon became clear why the CO was eager to have them on board. While the other pilots in 242 Squadron went out on leave passes, the Australians remained behind, doubled up on readiness duty. There were only so many ways to pass the time on readiness. Pilots were confined to their dispersal areas, wearing flying boots and Mae Wests, ready to leap into action on the off chance a scramble was called for the quiet skies of RAF Drem.

“The atmosphere just stinks in A flight 242 Squadron. I don’t like these dumb, artificial, fleshy faced kind of Englishmen, bits of pains in the neck ... will be mighty glad when 453 squadron gets underway.”

- Len Hansell

Two other Australians joined in at RAF Drem with apparent postings to 453 Squadron, Dick Ford and Bob Kenyon. However, Bob Kenyon wouldn’t last too long before being posted to other duties. Both of them had previously been posted with 457 Squadrons and were both rumoured to have been kicked out.

The squadron finally had a CO when Squadron leader Francis “Tony” Morello, a British RAF officer, arrived in an Avro Anson on June 18th with another Australian pilot in tow. With piercing black eyes, he was the picture of a typical fighter pilot to the waiting Australians. Despite the good first impressions, the Australians once again felt that they were starting on the back foot upon discovering that their new CO, though very experienced in Hurricanes and Tomahawks, had no experience flying Spitfires.

Before stepping into the role of CO of 453 Squadron, Tony Morello had fought an intense tour of operations during the Battle of Malta as a flight commander with 249 Squadron. After a stint as the CO of 112 Squadron based in Egypt, he was tour-expired and served out an operational break as a Chief Flying Instructor at 59 OTU.

Also at 59 OTU was a young Australian Pilot Officer named John Barrien. After completing training, John Barrien was struck down with tonsillitis. Well before the days of antibiotics, he was sent away for a tonsillectomy. Fully recovered, John returned to 59 OTU only to find that the rest of his course had already received their postings. With no new posting, John waited at 59 OTU as a staff pilot.

Staff pilots led formations and advised new pilots during training. This role also involved a lot of routine paperwork, which is how the signal ordering Chief Flying Instructor Morello, to proceed to RAF Drem to form a new RAAF Spitfire squadron had come through John's hands. Seizing the opportunity, John grabbed the signal and rushed to Morello, saying “Me, me, me,” and soon managed to secure his posting to 453 Squadron.

An article from a Queensland newspaper announcing a new Australian Spitfire Squadron being formed in Drem. Source: Trove

It had been 10 days since the first group of Australians arrived at RAF Drem, and things weren’t good. There was a clear dent in the group's morale as they sat around 242 Squadron drawing the short straw. After airing their gripes to George Hill, a new Canadian Flight Lieutenant who had been posted to 453, Tony Morello decided to get the Australians out of 242 squadron by officially forming 453 squadron on June 22nd with all the available manpower they had.

All nine pilots … and not a single Spitfire between them.

They did what they could under the circumstances. With no Spitfires, they spent the remainder of the afternoon shooting through their monthly allocation of 5000 cartridges on the clay pigeon range and stuck inside the dreaded link trainer.

Excitement wasn’t the only thing in the air the next morning, as the roar of Merlins announced the delivery of the squadron's first aircraft: eight Spitfire Mk.Vs, six of them brand new. Much to the delight of the pilots, they came equipped with the B wings, which replaced the four inboard .303 Browning machine guns of each wing with two Hispano cannons firing a punchy 20mm explosive round. As an indication of the equipment preference that second line squadrons received, there was a sprinkling of De Havilland airscrews with duralumin metal blades among the more common Rotol airscrews with Jablo wooden composite blades.

Unfortunately, the squadron was grounded the next day by the "scotch mist" setting in. The mist was a combination of thick fog with drizzling rain. When it set in it could shut down flying for a number of days. With the ground crews working on the Spitfires, the pilots again split their time between the range and the link trainer.

The link trainer was an early flight simulator that helped teach pilots “blind flying” techniques by purely relying solely on their instruments. With the lid closed, the “aircraft” would move using pneumatics, mimicking real flight. Pilots would listen through earphones to receive instructions from their instructors on courses to follow. Their progress (or lack of), was charted out on a graph by an electronic tracker. This setup allowed the instructor outside to communicate via “radio”, making course corrections when needed, and then review with the pilot their actual flight path vs the instructed one at the conclusion of the exercise.

The link trainer in its closed position rendering the trainee “blind”.

Source: AWM

The instruments and rudimentary controls of the link trainer.

Source: AWM

A trainee about to be closed up in the link trainer by his instructor.

Source: IWM (A 6039)

Course instructors stand by the microphones and plotting desks as trainees are locked into their trainers.

Source: AWM

The scotch mist and the high hills around RAF Drem made perfecting the ZZ Approach (Zero visibility at Zero height) essential. No pilot would want to practise such a challenging procedure in real conditions, but there was always the possibility that a quick-rolling mist could be waiting to greet him on the way back.

If a pilot were to descend into the mist, he would find himself without any visual cues regarding direction, altitude, or orientation. This required the pilot to navigate through the challenging conditions solely using instruments.

The ZZ approach began with the airfield controller guiding a pilot to the airfield at a specified altitude until the aircraft was overhead. The controller then provided an outbound course to follow and a safe altitude to descend to. The aircraft was tracked using direction-finding bearings every 30 seconds to ensure the pilot stayed on course. This heading was maintained until the pilot reached a predetermined distance from the airfield. At that point, the pilot was instructed to execute a “Rate One turn” (3 degrees per second) for a specified duration, which would theoretically align the aircraft with the correct heading for the airfield's downwind runway.

To ensure the aircraft stayed on the correct approach, the controller would continue the direction finding checks and instruct the pilot on their descent rate until the aircraft was on final approach to the runway. The last check before landing involved the controller (hopefully having a long microphone cable) sticking his head out the window to listen for the approaching aircraft. If the aircraft could not be heard, the pilot was told to “open throttle and climb away”. Otherwise, the pilot would be given the “Ok to land ahead” while everyone on the ground held their breath with fingers crossed.

RAF 'ZZ' Controlled Approach Procedure Diagram (From AP3024 Flying Control in the Royal Air Force - 1944)

Source: http://www.island-images.co.uk

Two days later, the squadron took to the skies as the mist finally lifted. With a careful strategy for maintenance, only three of the new Spitfires were flown on the first day. This strategy helped spread out the servicing schedules, ensuring there was never a time when all of the squadron’s aircraft needed to be grounded simultaneously for routine maintenance.

Each flight, the pilots pushed their new aircraft closer to the limit, trying to understand how far they could take the Spitfires and each other. They practised close formation flying, taking turns to lead through climbs, dives, aerobatics and the reduced visibility of flying through clouds. It was hard work. Pilots found themselves covered in sweat from a mix of summer heat and intense concentration.

On one of the training flights, Len Hansell found himself in close formation with Freddy Thornley, only a few feet apart, when suddenly he was hit with a rush of panic. He couldn’t see. His eyes were blinded as sweat dripped down his forehead. In that brief moment, as he wiped his eyes, Len’s Spitfire crept forward. When he finally cleared his eyes, he saw the yellow blur of his propeller tips spinning menacingly close to the underside of Freddy’s Spitfire.

Len shoved his spade grip forward to avoid disaster. He felt his Spitfire being thrown about by Freddy’s slipstream. The manoeuvre was so violent that his engine temporarily cut out, the negative G’s starving the carburettor of fuel. The sudden drop lifted Len out of his seat and added insult to injury as his head received a solid blow against the Perspex canopy.

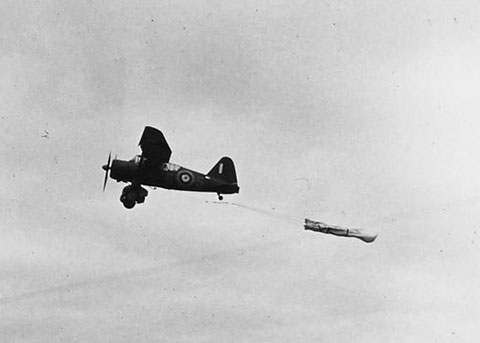

The Squadron soon began practising air-to-air firing. Between the 453 and 242 squadrons, they shared the station Lysander to hook up a 20ft canvas target drogue. The pilots' rounds were dipped in different-coloured dyes, which indicated the accuracy (or lack of) of each pilot's gunnery. Being the pilot of the Lizzie (nickname for the Lysander) was considered by some to be the worst job in the air force. They were forced to stooge back and forth between the mouth of the Firth of Forth estuary and St Abbs Head, while pilots practised their shooting skills on a target a few hundred yards behind them. The training pace picked up once equipment was available to tow a drogue behind 453’s own Spitfires, though it’s unlikely that this made the role of the target tug pilot any more popular..

A Lysander moments after deploying the target drogue.

Source: IWM (CH 4876)

An air ministry photo showing a pupil examining his shooting results.

Source: IWM (CH 6461)

At this point, the squadron clearly lacked experience. S/L “Tony” Morello had completed a successful tour of operations. F/Lt George Hill had arrived with just 2 months of operational flying with 421 Squadron RCAF. Dick Ford had only been operational with 457 Squadron for just over two weeks, with a total of 5 trips over France. Everyone else who had arrived and those still to arrive were straight from Operational Training Units (OTUs).

Over the 7th and 8th of July, three experienced Polish pilots were temporarily posted into the squadron to help bring the Australians up to operational standards.

The relationship with the Poles was similar to the student/instructor dynamic the Australians had all experienced over the past few years of training. There wouldn’t be any close friendships, but at the same time, the Australians understood that the Poles' entry into the war was very different from their own. They knew that the Poles' homes and contact with family were lost, and they couldn’t strike up a regular conversation about “their girl back home.”

At the same time, the Poles were there for one purpose only: to bring these young Australians up to scratch. They were exacting teachers, tough on their pupils. They had to get the Australians ready to enter the fierce arena of operations in the southern sectors, and they weren't afraid to push their pupils to the limits to achieve that.

“I slipped into tight echelon as he nosed over, felt the control tighten as the airspeed built up, down in a gentle dive around 300mph, skittled right across east fortune aerodrome about 500 ft, then right on the deck, hedge hopped to the coast, then over the cliff and down on to the sea, around an isolated rock past hundreds of seagulls, then up to cloud level again - What an introduction!

We stooged over the Cheviot hills, right up a deep valley skimming the tree tops, took almost six inches of boost to clear the brow of the hills. Pretty fair formation landing. These Poles are really hot fliers; all learned in Poland and are typical fighter types, lean, lithe and keen sharp faces, very dapper. We’ll need them in our squadron to go to 11 Group.”

- Len Hansell

The training continued, the formations were flown tighter and lower and the aerobatics were pushed to more extreme, more violent levels. Each pilot crept closer and closer to the limit when, on the 28th of July, Jim Ferguson found it.

It was a pristine day, no wind with clear, bright, sunny skies. Flying Officer Sobeicki decided to teach Jim something new by showing him the dangers of flying over still water. Sobeicki led the pair out to the entrance of the Firth of Forth estuary. The water was perfectly still, glassy, reflecting a perfect mirror image of the blue sky above.

With strict instructions to fly no lower than himself, Sobeicki led the pair down to the water's surface. Skimming just above the water, Jim Ferguson watched as the horizon (an important visual reference for a pilot when low flying) seemingly disappeared. The water mirrored the sky so perfectly that it was nearly impossible to tell where the water ended and the sky began.

The two roared above the water, heading out to the mouth of the firth before turning south again. As they passed Bass Rock, Sobiecki keyed his RT in alarm, letting out a cry over the airwaves that "Fergie's gone in!" Jim vanished as a large water plume shooting into the sky enveloped him.

Jim’s De Havilland propeller struck the glassy surface of the water. The metal blades dragged heavily through the sea, pulling the nose of the Spitfire downward. Each revolution was one step closer to a blade catching and flipping the Spitfire end over end.

The violence of the action also threw the Spitfire off balance, causing it to roll to the side. The pitot head, which extended a few inches beneath the port wing, disappeared in an instant. Torn off the moment it touched the water. If the wing dipped any further, it would almost certainly suffer the same fate.

All of this occurred in a fraction of a second. A lifetime of fast reflexes, hand-eye coordination and some bloody good luck saved Jim that day. In that split second before disaster, he pulled back on the stick, emerging from the massive plume of water to the surprise of Sobeicki.

Sobeicki managed to get the pair back to RAF Drem, which was no easy feat with Jim’s Spitfire responding less than favourably. The evidence of how close he had come to death stared Jim in the face as his airscrew came to a stop. A foot of each propeller blade had been bent back 90 degrees, pointing right at him. The incident left both Jim and Sobeicki shaken and was perhaps too good an example of the dangers of flying over still water. Though it wasn't enough to stop Jim's friends from accusing him of trying to join the submarine service.

Later that day, Chuck Fowler, who was being led in close formation by F/O Jankowski, burred the ends of his wooden Rotol propeller blades when he flew too close to his flight commander. Jankowski didn't come out of it unscathed, returning home with chunks missing from his rudder. Not a good day to be a propeller in 453 Squadron.

The next day, understandably concerned by the series of accidents, S/L Tony Morello called the squadron together to address poor flying discipline, mainly focusing on Jim Ferguson's accident. Based on a suggestion from F/Lt Hill, the discipline started on the ground, with all the pilots now showing correct military respect for authority by addressing all officers “Sir” or “Mr.”

Many pilots arrived at 453 Squadron in groups from different OTUs, some had been with each other from the first RAAF training school in Australia, others had known each other since high school. After earning their wings, promising pilots received commissions as Pilot Officers, while the others graduated as Sergeants. The Australians were informal with each other, disregarding such regulations. The Royal Air Force (RAF) at the operational squadron level was known for its relaxed atmosphere, where the use of first names and nicknames was common, even among senior ranks up to the Wing Leader. Some believed this informality stemmed from the RAF being a relatively new service compared to the Royal Navy or the British Army, which had more established customs and traditions.

The resultant order went down like a lead balloon.

Some of the sergeants acted as if they had never heard the order. Some, including the RAAF officers, treated it as a big joke. Others ignored the officers entirely, refusing to engage in conversation and acting as if they weren’t present. The bitterness created a rift within the squadron.

“Popular man” described one of the sergeants of F/Lt Hill. “Guess he’ll have to get to understand Australian psychology a little better if he is to make a success of running an RAAF flight.”

Dick Darcy, one of the Australians who had passed out as a Pilot Officer, was among the first to extend an olive branch to the Sergeants of B Flight. He joined Jim Ferguson, Jim Furlong and Matt De Cosier in Len Hansell’s room for an airing of grievances. Just as Len was about to launch into a "seditious oration,” Wilfred Whiteford poked his head into the room. The CO wanted to talk to him. With visions of being court-martialled, Len was shocked by an irony of ironies when Morello told him that he had just been recommended for a commission!

Despite F/Lt Hill's suggestion to improve flying discipline, the accidents continued as the inexperienced pilots worked hard to bring themselves up to operational standards.

"453 was a proud but unique Squadron, taking its pilots from the various OTUs, the majority being NCOs, they would work up through the ranks and then, commissioned. Amongst ourselves the Officers were referred to as "highlies"', NCOs as "Iovelies" and Airmen as "erks". There was no disrespect whatsoever in these terms."

- Fred Cowpe, talking of the squadron formalties during his active period betwen late 1943 to mid 1944

Out of the groups of pilots who had arrived at Drem, none of them had known each other as long as David “Chuck” Fowler, Charles "Guy" Riley and David “Spit” Steele. They were Adelaide boys, high school friends. All of them had attended St Peter's College together; they were all in Farrell house and each of them had spent four years in the college cadet corps.

A group from St Peter's, including the three, had signed up to the Citizen Air Force/Air Force Reserve while they waited for positions to become open in the Empire Air Training scheme. This allowed them to attend one of the Initial Training Schools while they waited. When the positions for Air Crew in the full-time Air Force finally became available, they received their application forms, but being under 18 they still had one daunting step - facing up to their parents.

“I had to get permission from my parents to join the services because I was under-age. I asked my father to sign and expected a bit of a discussion but no, he took it and signed it right away. Because he knew quite well, and previous to that he and my mother must have discussed the fact, that I wanted to join up”

- Jim Ferguson

Each of them presented their parents with their completed RAAF Application for air crew forms on 19th of September 1940. Each parent signed and dated the application in front of them, likely feeling a mixture of fear and apprehension about the dangers their sons were about to face.

The group's plan to remain together had been successful so far. They first passed through No. 1 EFTS in Tamworth, Australia, then moved on to 14 SFTS Alymer in Canada, followed by 17 AFU at RAF Watton and 53 OTU at RAF Llandow. Eventually, they arrived at RAF Drem, posted to 453 Squadron. They were fortunate to stay together for so long, as the military often assigned personnel wherever needed, with little personal choice. Less than ten days after their arrival, 13 Group HQ contacted S/L Tony Morello, requesting that 453 Squadron transfer two pilots to 242 Squadron, who were also based at Drem. Chuck Fowler was one of them.

The squadron attempted to fight it, with both Morello and Fowler submitting requests to return him to 453. Headquarter Fighter Command reasoned that they had requested Australian aircrew to join 242 Squadron, and Fowler had simply been chosen because he was already at RAF Drem. While they didn’t send him back to the squadron, they admitted it was undesirable to pull Australian aircrew away from an Australian squadron and said they would make every effort to repost Fowler back to 453 Squadron.

St Peter's College army cadets in a march past during a camp at Woodside, South Australia, 1938.

Source: State Library of South Australia [B 62861]

Squadron ORB Item 2: S/L Tony Morellos concern over the posting of 2 pilots to 242 squadron and negative impact it had on pilots sense of solidarity during such an important time.

Source: NAA: A9186, 139

On the 1st of August, Guy Riley and Spit Steele went out to practise dogfighting and aerobatics. The two had concocted a theory to test, something to gain the edge in a dogfight. The plan was to try and drop the Spitfire's landing flaps as a defensive manoeuvre with the hope that the attacking aircraft would overshoot and zoom past the defender.

The concept of using flaps in combat wasn’t anything new, however it wasn’t a safe tactic in the Spitfire. Unlike most other aircraft, the Spitfire's flaps didn’t allow for any angle of adjustment. It had two positions, up or down. As a result, the Air Ministry pilot's notes for the Spitfire Mk.V limited their operation to indicated air speeds of 140mph or less.

The two of them flew north of the Firth and climbed up to 15,000 ft. They started practising attacks on each other, dropping their flaps, trying to force the other to overshoot. About 30 minutes in, Spit Steele's cockpit canopy cracked open and dangled on the R3002 IFF aerial. Spit tried to call up Riley to tell him he had to return but his RT microphone was experiencing issues and got no response.

Within 10 minutes of returning to Drem, operations rang through, they asked 'Spit' if he knew where Riley was. After telling operations that he had last seen Riley climbing through 11’000 ft North of the Firth, he received heart wrenching news that an aircraft had been seen to crash in the same area from a great height.

The aircraft that had come down and crashed into a farmhouse. Luckily for the occupants, they had been in the garden at the time. The pilot was identified as P/O Charles Riley.

The inquiry that followed found that while the Riley's Spitfire had fallen from a significant altitude, the damage sustained to the aircraft indicated that its speed had not been high. The flaps were found to be in a down and locked in position. The use of flaps was also questioned seriously as it went against operating procedures directed by the Air Ministry. Picked at random, Dick Darcy and Rusty Leith were called to give statements that they had been provided with the correct pilot's notes and operating instructions for the Spitfire Mk.Vb.

Two witnesses of the crash came forward to testify in the inquiry. They had seen Riley’s Spitfire came out of cloud in a shallow spin. They had heard roars from the Merlin engine as Riley made attempts to increase power to recover from spin. Falling to 2000ft, it looked as though Riley had managed to stop the spin but moments later the aircraft lost control again, spinning away in the opposite direction. At the last moment, just 200 ft off the ground Riley appeared to have stopped the spin, it coincided with another roar of the Merlin at full throttle but it came too late. The Spitfire nosed down and struck the farmhouse in a vertical dive.

At the conclusion of the court of inquiry two investigating officers concluded the following:

"In my opinion the pilot commenced a practise spin at a height of 8,000 - 10,000 feet. Either he had his flaps down or he failed to pull the stick right back, with the result that a flat spin occurred. It took a considerable time to make a recovery which was effected by putting the aircraft into a normal spin. I consider the pilot had insufficient height to gain a safe flying speed before pulling out of his dive, thereby stalling at 200 feet.In my opinion the accident was due to inexperience on the part of the pilot when executing that manoeuvre. I think that flaps were used intentionally though the pilot was inexperienced in their use.”

“All the evidence points to the fact that the two pilots concerned had discussed the possibility of the use of flaps and ignored the orders on this subject presumably thinking they knew better.It is quite apparent that the handling notes and pilot orders were read as the evidence of the squadron commander and two pilots chosen at random.”

Understandably, the death of Guy Riley deeply affected Spit Steele. He had already lost his brother Geoffrey in February, flying with 211 Squadron in Sumatra, Indonesia. Geoffrey had been on convoy escort duty with two other Blenheims - All three were shot down by fighters, with only two survivors out of the nine crew members who went out that day.

After travelling across the world on a great adventure as a band of three high school friends, it must have been a painful adjustment for both Spit Steele and Chuck Fowler when, ten days later, Chuck left RAF Drem with 242 Squadron for RAF North Weald.

The following day, the unease caused by F/Lt. Hill's orders still lingered. More scotch mist rolled in, leaving the squadron grounded again for several days. But the time on the ground created an opportunity for the Australians to come together. After five days, the Australian Pilot Officers and Sergeants reached a clear understanding.

For the Sergeants who suddenly had to treat their mates differently, it was a humiliating order. The Pilot Officers supported the sergeants and made it clear they were against the order. Demonstrating solidarity, and no doubt to the delight of the sergeants, Pilot Officer Dick Darcy confronted F/Lt. Hill and gave him a few home truths. By the next day, the Australians observed a significant boost in morale throughout the squadron, with the exception of a seemingly subdued F/Lt. Hill.

On August 5th, F/Lt John Jack Ratten arrived at the Squadron and took over as the Flight Commander of A Flight, bringing a wealth of experience from 72 Squadron. He gave the squadron a general talk on operations and tactics learned from over 70 sweeps of occupied territory. He was the first Australian to become a flight commander and a significant step to the squadron taking hold of its Australian identity.

A few days later, Air Chief Marshal Sir Sholto Douglas, the Air Officer Commanding, arrived. Meanwhile, the pilots had spent the previous day lining up in an emu formation, collecting any stray objects around the 453 Squadron quarters. While the AOC asked S/L Morello many pertinent questions, some pilots felt that “Sir something Douglas, bags of bulsh” looked down on the Australians as if they were a flock of cull sheep. Most notably and disappointingly for the pilots, he did not mention anything about moving the squadron south to one of the active sectors.

The 12th of August began with the news that F/Lt Hill, who had just gone on leave, had been transferred from the squadron. The quietly spoken but capable Russ Ewins took over as acting flight commander of B flight until a replacement could be found. The day went on to more excitement of a different kind as the reality of the war came crashing down on 453 Squadron.

The sun didn’t set until 10:30 pm around Drem in August. At 9:30, as dusk was settling in, the airfield lights went out and the sirens started to blare. The tannoy crackled an announcement across the dispersal areas: “Deacon aircraft scramble! Enemy aircraft approaching!”

The pilots on readiness duty from A flight sprang to their feet, sprinting to their Spitfires in what was about to become 453 Squadron’s first operational flight. Two sections went up: Sergeants Jim Furlong and Rusty Leith as Red 1 and 2 and Sergeants Dick Ford and Bob Clemesha as Yellow 1 and 2.

L-R: Jim Furlong and Rusty Leith

Image courtesy of friend of the website www.rustyleith.com

For Red and Yellow sections, the view at 13,000 feet was clear as day. Below, the increasing shadow of dusk was taking hold. After half an hour, two specialist nightfighter Bristol Beaufighters from 410 Squadron RCAF were scrambled from Drem to scour the ever-dimming lower altitudes.

Meanwhile, the remaining pilots gathered around the dispersal areas in the hope that the situation might evolve into a squadron scramble. Jack Ratten sat in one of the Spitfires with the RT on, providing a running commentary to the pilots propped up and around the Spitfire.

Ground Control Intercept (GCI) took over the movements of red section as they tried to align their radar plots to position the Spitfires on a vector to intercept one of the bandits. Meanwhile, in yellow section, Bob Clemesha reported that Dick Ford was returning to Drem after Dick had managed to signal to Bob that his RT was not functioning. Without a radio, he would be unable to navigate home once night fell.

Back at Drem, Jack Ratten was excitedly calling out updates from his Spitfire. “One of the bandits is 4 miles ahead of Red section!”

About this time, Len Hansell, propped up on Ratten's wing and listening to the commentary, noticed a twin-engined aircraft, which he pointed out to the A flight Fight commander.

“It’s a #!* 88 too!” exclaimed Ratten.

“It’s a Beau, not an 88,” retorted one of the other pilots. Both aircraft were twin-engined types, and in the low light, they presented a similar silhouette.

In the background, as Dick Ford arrived back at the airfield, he signalled for the Drem lights to be turned on. Following the circle of lights until he reached the threshold, he turned in and made a perfect landing through the quarter light of the setting sun. Watching Ford taxi to the end of the runway, the twin-engine aircraft appeared again, making a gliding approach down the flare path of the active runway.

“Must be one of the Beaus returning with issues as well” theorised one of the pilots.

“That’s an 88” stated another pilot.

“It’s a Beau … no, an 88” chimed in another pilot.

“No, a Beau” a different pilot countered.

“Famous last words” commented Rattan over the top of the debate “It’s “only” a Beau.”

“Well, we’ll soon find out,” said Dick Darcey matter-of-factly.

They did, and it wasn’t a Beaufighter.

Air ministry recognition images of the Beaufighter and the Junkers 88. In low light conditions, faced with the front on silhouette it’s easy to see how the personel at RAF Drem got confused.

“LOOK OUT!!” roared Hal Parker, “HE’S DROPPING BOMBS!!”

He needn't have bothered; every pilot had already dived for cover as soon as they saw objects falling from the twin engined aircraft.

Jack Ratten, without enough time to get out of the cockpit could do little else but make himself as small as possible as he slid down as far into his seat as it would allow.

Jim Ferguson, who had spent the previous days in an emu line tidying up the field for the imminent arrival of a press contingent, found that:

“I was lying on the grass, I never knew I could lie so flat, because the stuff whistling over the top of me was only coming from about 20-30 yards away. The grass had just been cut and to me it looked about 3 ft high!”

S/L Tony Morello had recognised the aircraft as a Ju88 on its first pass and immediately went inside to report it to operations. He was just coming out the door when the Ju88 returned and the first bomb exploded. After the raid, he said he was on the ground before any of the shrapnel arrived. Spotting a nearby table, Morello moved over to it with the intention of using it for cover. But he wasn’t the only one who had the idea. He pulled up to the table at the same moment as one of the Sergeants. The Sergeant, recognising the CO, stepped back to allow Morello to take the piece of cover. Morello, waving the Sergeant under the table, stated firmly that “We look after ranks here, Sergeant!” A moment later, the second bomb went off and the two men dived under the table together.

Dick Ford had just taxied off the runway when his Spitfire was hit by shrapnel. Luckily, none of the shrapnel hit him or anything important in the Spitfire, but it left behind jagged holes along the side. With no RT working, he had no idea what was happening or if any more attackers were coming. Doing the smart thing, he leapt out of his Spitfire and dived for cover under the nearest vehicle. He didn’t feel quite as smart when the bombs stopped exploding and he realised he had taken cover under one of the fuel trucks.

Three bombs detonated across 1 Skipway, causing injuries and damage. Two Airmen sustained superficial injuries, but remarkably, 453 Squadron escaped unscathed despite the shrapnel flying around them. The blasts destroyed a dispersal hut, a drying room, a latrine and damaged the Control building. Bomb disposal units were called to deal with three bombs that did not explode. One of the damaged buildings in the 453 area was already scheduled for demolition, so the Squadron considered themselves to have come out on top.

The remainder of Red and Yellow sections were directed to land at RAF East Fortune, returning the next day after a large emu line of personnel crossed the airfield,picking up shrapnel. A few of the pilots took advantage of the situation and gathered mushrooms at the same time.

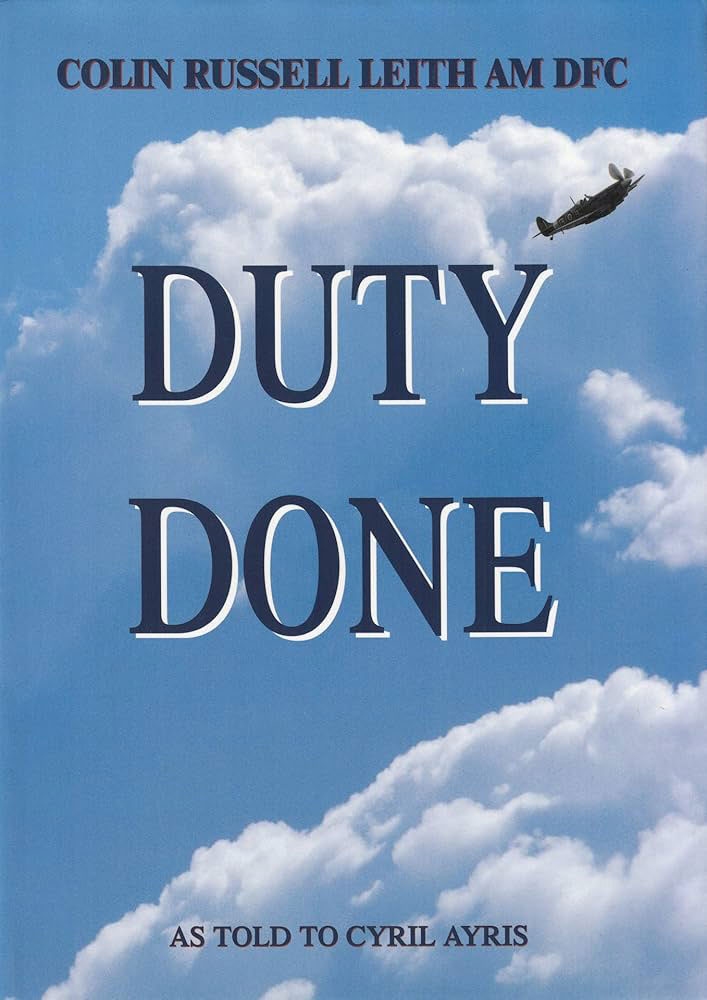

You can read Rusty Leith's account of that first scramble and the potentially fatal mistake he vowed never to repeat in his biography 'Duty Done,' available on Kindle.

If you wish to learn more about Rusty, you can read about him from friend of the website www.rustyleith.com

“Spitfire guns are loaded from the bottom of the wing but why worry. Perhaps that’s why the chap on the wing is laughing” - Jim Ferguson

Pilots L-R: Bill De Cosier, Jim Ferguson, Jack Stansfield

On the 14th of August, 453 Squadron was announced to the world after the public relations officer for 13 Group invited "practically every newspaper in Australia and most of Scotland.”

S/L Tony Morello led five other pilots in a formation flight. The pilots kept their eyes fixed on the aircraft next to them. Only those beside the CO dared to look for their leader, as they maintained a tight formation. They were bumped about by each others slipstream, streaking low across the airfield in the hope of a good snap for the photographers.

After the formation flying, the press had pilots pose for photos in the usual style of heroic, intrepid airmen ready to do battle with the enemy. Some pilots “shot a wicked line” with the reporters who stayed for dinner. Others, uncomfortable with the attention and publicity, avoided them.

Photos were available for pilots to purchase from the photographers. An article featured in the Scotsman can be read below.

The Scotsman 19 August 1942

AUSTRALIANS SPREAD THEIR WINGS

Visit to a New Fighter Squadron in Scotland BY OUR AERONAUTICAL CORRESPONDENT

Although outwardly the big R.A.F, station is like most R.A.F. stations, not particularly beautiful architecturally but suited to the job, at the dispersal huts occupied by the Australian fighter pilots one sensed a change from the ordinary. It wasn't the display of beetroots and cabbages outside, common enough about many Service huts these days. I suppose the Australian democratic indifference to formality had much to do with it. At any rate, I do not think I have ever seen airmen and newspaper representatives getting together so quickly and easily. They are a young eager lot, these members of the Royal Australian Air Force who have recently come to Scotland flying Spitfires. They wear distinctive dark navy blue uniform with an extra "A" added to the R.A.F. monogram between their wings. They have the old-young experienced look, the clean-cut features of most men from "down-under." They are desperately keen to bag their first Hun. One of them, a sergeant pilot, has already had his first visual contact with a Junkers 88 among the clouds in Scottish skies. On routine flying or during a "flap" they are as eager to get up into the air as some people are to get down. They love their Spitfires, although, being "Aussies" they don't express themselves that way. Their language, in fact, is startlingly forceful.

TRAINED IN CANADA

Their squadron, which was formed in June and became operational last month, is the only unit of the R.A.A.F. flying Spitfires in this country. Most of the pilots have graduated from the vast airmen's pool of the British Commonwealth Joint Air Training Plan, the official name for the Empire Air Training Scheme. Others have come via the training schools of Rhodesia. I asked a sergeant pilot from Adelaide how he liked flying a Spitfire. "Great," he said. "They're great kites. But I didn't fly mine first time. It flew me around." I was visiting the Australian airmen by invitation of the Air Ministry. One of the most impressive features of the visit was their elaborate display of formation flying. I have seen nothing better in station keeping in the air since the pre-war Hendon shows. There is said the Australians, but the Canadians in the audience seemed "frightfully bored." Another of the flight commanders is a Flight Lieutenant of South Australia. He was shot down three times in the Battle of Britain, and each time made a safe landfall. Against these discomforts he has seven enemy machines to his credit.

POLISH PERSONALITIES

I remember being told by a very senior R.A.F. officer early in the war that Empire pilots, with their dash and imperturbable outlook, provided an excellent "leavening." In the same way, apparently, war-experienced Polish pilots, men of quick violence in the air, have a similar effect. At any rate, there are three dashing Polish pilots with these Australian fighter boys. They are young in years, but old in war experience. One Flying Officer, who is 23, joined the Polish Air Force three years before the war. After the Polish upheaval he escaped into Rumania, but was imprisoned. He escaped, travelled to Beirut, and thence to Marseilles. He served With the Polish forces in France and after the collapse in that country, reached a Spanish port and sailed to North-East Africa. Then he journeyed to a West African port, got a ship for this country, and in more recent times has been flying with a Polish squadron in day sweeps over France. Flying from a Midlands aerodrome in the spring of this year, he encountered and severely damaged a Ju88.

MAINTAINING FIGHTING TRADITION

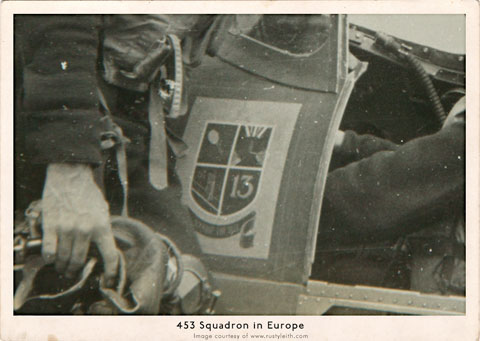

And what of the young Australians themselves , men who are maintaining the fighting tradition so gloriously established by the Australian Flying Corps in the last war, and being maintained daily by the R.A.A. F. in this. In the last war the only Dominion forces were the Australians with three squadrons in France and one in Palestine, and the South African Aviation Corps, which operated throughout the campaign in South-West Africa. Against a background of cannoncarrying Spitfires, to say nothing of beetroots and cabbages, I met among others, the son of an Australian senator, an optician in civil life, a former bank clerk, a sheep farmer, engineer, motor mechanic (a sergeant), who went as a boy to Australia from Glasgow 18 years ago), a stock agent and a woolbroker (who had previously served in the Light Horse.) "Home towns" mentioned were Brisbane, Canberra, Ballarat, Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide, Newcastle, and others, representative indeed of the four corners of the island continent. We talked flying and cricket. From what I gathered, this particular Scottish air station seems likely to be the venue of several minor Test matches. Or:e hefty youth sought information on salmon fishing in Scotland. Others were looking forward to seeing something of Edinburgh's historical and other attractions. A member of the ground staff enthused about the breakfast mushrooms the aerodrome provided. Several spoke appreciatively of the speed and regularity of arrival of mails from overseas. Scotland indeed seems to meet with the Aussies' full approval, and the pilots have a special word to say about the pleasure they have flying over a beautiful countryside of wide farm lands. They are all eager to meet Scots at home. One native, a Scots collie pup, has already established himself as an unofficial mascot. As we left these cheerful young fellows, representative of the steady flow of highly skilled airmen now reaching this country, one insisted on showing me the "crest" on a Spitfire near the tarmac. It seems symbolic of the R.AA.F. 's spirit. It showed, among other items, representations of a cracked mirror, a cigarette being lit with three matches, a pedestrian walking under a ladder, and the figure 13. Below was the slogan, "So what the hell."

The crest referenced by the reporter featuring a broken mirror, three cigarettes being lit by a single match*, a pedestrian walking under a ladder and the number 13. The "motto" says "So what the hell"

About to play two up?

L-R: Ben Nossiter, unkown, Freddy Thornley, Spit Steele, Dick Darcy, Jim Furlong, Bill De Cosier, Len Hansell, Bob Clemesha, John Barrien, Tom Swift, unknown, Jack Stansfield, Unkown

By the end of the day, the Squadron had lost all their Spitfires as 222 Squadron, which had replaced 242 Squadron at Drem, took them to take part in what became one of the war's largest aerial battles, Operation Jubilee. In return, 222 Squadron left 453 Squadron with some very battle-worn Spitfires, troubled with issues.

You, the reader, may have noticed that many of the photos feature Spitfires with the squadron code “FN” painted on the side (or perhaps not). A Spitfire’s primary markings include two sets of codes: a two-character code indicating the Squadron (in this case "FN") and a single character indicating the individual aircraft itself.

It hasn’t been definitively clarified why 453 Squadron used the squadron code “FN” for most of their time at Drem. “FN” was the squadron code used by 331 Squadron (Norway). Russ Ewins logbook as one of the earliest members of 453 squadron shows that the FN code was in use from his first squadron flight on June 26th 1942.

Some have speculated that the Spitfires had come from 331 Squadron, however the Spitfire production list available from www.airhistory.org.uk does not show any Spitfires arriving at the squadron until October 1942 when the Squadron had left Drem.

The delivery of the first Spitfires may have come from, or been intended for, 331 Squadron, with the “FN” squadron codes already applied. With no squadron code assigned to them, 453 may have continued using “FN” until they were assigned their own code. According to logbooks made available, the transition from the “FN” to the “FU” squadron code, which 453 Squadron would become famous for, happened around August 19th, 1942.

As pilots established themselves in the squadron, they often received their own individual aircraft and identifiers. Don Andrews, who joined the squadron at Hornchurch, was known for flying Spitfires marked with “FU-?”. Russ Ewins was the principal pilot of “FU-S” for Sylvia, Dick Darcey FU-X and Jim Ferguson “FU-U” to name a few.

Author's note: Apparently, there are rude implications that can be drawn from the squadron code “FU” and stretched even further when combined with the individual aircraft codes. But "FU-K"d if this amateur researcher can figure out what they could be? Regardless, we can be sure that a group of Australians in their early 20’s would definitely not have taken part in that sort of thinking ... who am I kidding.

222 Squadron returned to Drem on the 20th with many lines shot of the big adventure they had had over Dieppe, leading to much “weeping and gnashing of teeth” by 453 Squadron on missing out on the show. Despite F/Lt Hill’s culture mismatch with 453 Squadron, he claimed two FW190’s over Dieppe and finished the war as a highly successful ace scoring 10 kills, 8 shared kills and 3 probables and 10 damaged.

On August 21st, 453 continued flying with 222's Spitfires while their own went under maintence. Len Hansell found himself in trouble when Dick Darcy led two sections out for battle formation practice. The Spitfires flew out out to sea at zero feet. Dick flying Blue 1, initiated a series of climbing turns to quickly reach a higher altitude. His No.2, Alex Blumer, and Len, leading Green section with Bill De Cosier as his No.2, struggled to maintain formation because Dick was the only one not flying one of the worn-out 222 Spitfires. After a demanding five-minute climb, both sections reached 10,000 feet, anxiously watching their engine temperatures climb.

Dick led Blue section up a further 3000 ft to prastise attacks, while Green section tried to cool their engines. Starting the battle practice, Blue section came in from Green's high 4 o’clock. Alex Blumer leapt on Len Hansell, who smashed forward his boost lever in a hard climbing turn. His vision started to grey as the G-forces took hold of him. The sudden increase in power had clearly been too much. Len’s engine began to run rough, vibrating the aircraft violently. Pulling out of his hard turn, he pulled back the boost and airscrew controls, hoping the aircraft would recover. But the violent vibrations continued.

After informing Dick of his situation, Len was swiftly ordered to RTB. He turned toward Dunbar, gently gliding his Spitfire to conserve engine life. Just after crossing the coast, the vibrations intensified to the point where Len feared the wings might come off! His hands gripped tightly as the Spitfires controls tried to tear themselves from his grasp. The situation worsened as black smoke billowed from the engine, completely obscuring his forward vision.

He slammed the boost and air screw levers back, then leaned forward to move the fuel cock to the off position before turning off all the switches around the cockpit. He pushed on the rudder pedals firmly, counteracting with his stick to put the Spitfire into a side slip in an effort to gain some forward visibility. Initially planning to land early at RAF East Fortune, he realised he had a tailwind and decided to extend his glide to RAF Drem.

Things went from bad to worse when his radiator finally boiled over and started spewing steaming glycol coolant in white clouds. Len felt panic levels rising as he realised he was now too low to bail out. Acting fast, he managed to drop his undercarriage and flaps before side slipping his way from 1000ft in a dead stick approach. Rolling across the field he swerved off and pulled up in front of A flights dispersal from which the Spitfire had been borrowed. Exiting the aircraft not a moment too soon, he turned around to see flames burst out of his engine. The ground crew leapt into action, dousing the fire with chemical extinguishers.

Len realised the CO must have been a bit worried when the usually reserved Morello praised his performance with a “Jolly good show Hansell old boy, jolly good show”.

After inspecting the engine, the crank case was found to have two gaping holes on each side. Either the crankshaft had failed, punching a hole through the case, or the pressure had burst a hole through each side. The unimpressed ground crew who were trying to maintain the worn 222 Squadron Spitfires commented that the engine was so old it had been worn out since the Battle of Senlac Hills (a.k.a The Battle of Hastings October 14, 1066).

_v2_tn.jpg)

"Its really quite simple" says the expert, but the A.T.C. lads find the Spitfire's Merlin engine far from a simple piece of machinery.

Source: IWM (CH 6442)

“We had a good rugby team, we had a very fast team. Normie Swift told me, he said “We’re the only team to ever beat ourselves”. We were playing for Hornchurch and were leading the competition and there was no finals, all you had to do was win the last game. In the meantime they moved us to Southend so we played (as) Southend, and we played Hornchurch so they didn’t win the premiership after all.”

The pilots' bonds started to strengthen both in the air and on the ground. Events were organised to reinforce these bonds, ranging from sports events and tourist trips into town, to good old-fashioned drinking sessions with dancing, sing-alongs and a healthy dose of mischief.

Mischief at Drem may or may not have included: Dick Ford chasing "all hands" around with a sword, Rusty Leith finding a minister's "funny flat hat, cape and walking stick" before passing around the collection plate to top up the beer kitty. Russ Ewins having a bowler hat full of beer slammed on his head. Tommy Swift clearing the bar in the Sergeants' mess of beer glasses when he threw a pillow across the room, or Tom having a pint thrown over him after his errant pillow spilled beer all over a flight sergeant.

Ten little fighter boys taking off in line, one was in coarse pitch then there were nine;

Nine little fighter boys climbing through the date, one’s petrol wasn’t on, then there were eight;

Eight little fighter boys scrambling up to heaven, one’s weaver didn’t, then there was seven;

Seven little fighter boys up to all tricks, one had a hangover, then there were six;

Six little fighter boys milling over Hythe, one flew reciprocal, then there were five;

Five little fighter boys over Frances shore, one's pressure wasn’t up, then there were four;

Four little fighter boys joining in the spree, one’s sight wasn’t on, then there were three;

Three little fighter boys high up in the blue, one’s rubber pipe was loose, then there were two;

Two little fighter boys homing out of sun, one flew straight and level, then there was one;

One little fighter boy, happy to be home, beat up dispersal, then there was none;

Ten little fighter boys nothing have achieved, AOC of group is very, very peeved;

Fifty thousand smackers thrown down the drains, cause ten silly baskets didn’t use their brains

-Song sung by 453 Squadron

Men of 10 Squadron RAAF serving with RAF Coastal Command playing rugby with a Sunderland aircraft in the background.Source:

Source: IWM (CH 4354)

On August 28th, Rusty Leith led Spit Steele in a battle climb up to 30,000 feet to practise dogfighting. Rusty lost sight of Spit at 20,000 feet but assumed he had slid into line astern and kept climbing. When he reached 30,000 feet, Rusty realised he was alone and attempted to contact Spit on the radio, but received no response. With no sign of Spit, Rusty returned to Drem.

Later that day, reports came in that a Spitfire had dived in and burned on the moors southeast of Haddington. Morello, Rusty, Danny Reid, and Smitz went out to inspect the crash site. The massive crater left behind was still burning from the bottom. The Spitfire's engine was discovered several feet beneath the soft soil. Fragments of the wreckage were strewn around the area for 400 yards, leaving no doubt of the speed and violence with which the Spitfire hit the ground.

A local who had witnessed the Spitfire fall from the sky described the aircraft diving sharply at high speed. Just before the impact, he believed he saw flames and smoke billowing from the engine.

The funeral for Spit Steele was held on the afternoon of the 1st of September with members of the Squadron as pallbearers. Only afterwards were they told that so little had remained of Spit that the undertakers loaded the coffin with weights to fill out the remainder.

No official reason was ever given for why Steele suddenly dived into the ground. The flames seen coming from the engine were attributed to a possible overrevving caused by excessive speed during the dive as he fell from the sky. This could have caused a crankcase failure, leading to a mixture of oil, glycol, and water, which might have produced the flames and smoke.

While not official, there was a generally accepted theory about what happened. John Barrien, also an Adelaide native, sent a letter home to his parents suggesting they contact Spit Steele's parents to offer their condolences. John's parents did just that; letter in hand, they followed the address and arrived at Spit’s parents’ house. Unfortunately for everyone, Spit’s parents insisted on reading the rest of the letter which along with the directions to their house included the line “The silly bugger didn’t turn on his oxygen.”

Some might view the line as callous, but it's important to remember that many pilots coped with the constant risk of death with the belief that "It won’t happen to me” or “I’ll never make that mistake.” In this case, John may have included the line in an effort to prevent his own parents from worrying, who were the original and only intended readers. The following quote from RAF Pilot Merton Naydler comes to mind.

“Of course, we did not think of dying; the other chap might, probably would, sometimes did, but it never happened to oneself, always the other poor bastard. For a magical voice whispered in our enchanted ears, “young man - you’ll never die!” It’s only when that voice falls silent that the superb confidence of youth is known to have passed, and one is wiser, if sadder”

Len Hansell remembered Spit as:

"A damn nice fellow was “Spit”, slightly auburn brown hair falling over a well featured freckled face, a generous mouth always ready to break into a new moon grin, big even teeth and a pair of strong blue eyes. Just a friendly cheerful real good egg. The squadron is poorer for his loss, we need men like Spit. He was a great cobber of Riley who went in under similar circumstances a few weeks ago. Chuck Fowler who usually made up the trio was transferred to 242 squadron soon after coming here and was shot up (wounded) in the Dieppe do."

In less than a month, the war had ground down the group of three high school friends from Adelaide to just one survivor recovering in hospital. Chuck Fowler returned from Dieppe and was taken to a hospital in Margate where he was listed as seriously injured. He never flew operationally again, his injuries had left him graded medically as A2B: fit for limited flying duties and ground duties. He spent the remainder of his time within the RAF at 1 delivery flight in Gatwick.

A group photo of St Peter's college students who had enrolled in the RAAF Reserve.

L-R: Chuck Fowler, D. W. H. Jones, Spit Steele, P. K. Wendt, Guy Riley, J. G. Hylton

Source: St Peter's old collegians Facebook page

For a short period, B flight was taken by John Cock an experienced Australian who had fought in the Battle of Britain, in quick succession he was posted out and the flight was taken over by the colourful F/Lt Harry Harrington, who had lost his rank as Squadron Leader and his squadron of Typhoons after a drunken mishap involving an Armadillo Armoured Fighting Vehicle and a water tank. Apparently forgiven by Group Command, he took charge of 222 Squadron a fortnight later leaving B flight once again leaderless.

A young Pilot Officer named Jack “Slim” Yarra was posted in on the 10th of September with only 270 hours of flying, including training. It made it all the more impressive that the “quiet, lightly built kid” arrived with 12 confirmed kills, six probables, several damaged aircraft, and a Distinguished Flying Medal.

"The C.O called in Barrien, Darcey & myself this afternnon to tell us that Yarra was going to take over "B". He is junior to us all, but his ops experience clearly outweights any question of seniority. Should be a good thing in the flight."

- Russ Ewins.

Slim participated in some of the fiercest aerial battles in Malta after taking a one-way trip in a Spitfire from the aircraft carrier HMS Eagle. For a brief period, he flew Hurricanes due to a shortage of airframes, but he soon returned to Spitfires to engage in intense combat as the RAF fought against both the Regia Aeronautica (Italian Air Force) and the Luftwaffe.

The citation for his DFM reads:

“This pilot has shot down 4 enemy aircraft in air battles. On one occasion, when protecting a rescue launch in the face of numerous enemy aircraft, he shot down 1 Messerschmitt and probably destroyed another. When his ammunition was exhausted he made feint attacks and kept the enemy at bay for three quarters of an hour.”

On the 21st of September, pandemonium broke loose in the dispersal room after the S/L Morello and the RAF Drem Station Commander announced “You’re going south on Friday the 25th boys.” Over the top of the excitement and whoops of joy, he followed up with “and maybe Spit IX’s” to more cheers and celebration. For some of the early members who had been at RAF Drem since June, it couldn’t come a moment too soon. They were heading to RAF Hornchurch.

On the 23rd, all flying was halted to ensure the squadron's Spitfires were ready for the move. The same day, P/O Catchpole arrived to become the squadron's first Intelligence Officer. He would be one of the few “poms” who would be a mainstay in the Australian squadron.

The officers organised a celebration for the CO, who received a silver tankard inscribed by the squadron members as a wedding gift. During the party, Alex Blumer lost a large bet by failing to drink a gallon of beer, while the quiet but focused Russ Ewins, cleaned up after drinking half a gallon in thirty minutes.

On the night of the 24th, a large part of the squadron left by train, filling the carriages with nearly all their equipment. The remaining pilots were supposed to travel the next day, but the scotch mist rolled, leaving them stranded at RAF Drem for another night.

On the 26th, 17 Spitfires finally departed from RAF Drem. F/Lt Ratten led the squadron, with Slim Yarra and Dick Darcy leading two other sections of four aircraft each. The remaining five aircraft formed an ad-hoc section led by Tom Swift; they flew separately but maintained visual contact with the main formation. The squadron stopped halfway at RAF Catterick to refuel, but had to leave two pilots behind after their Spitfires went unserviceable (U/S).

The final two Spitfires arrived at RAF Hornchurch the next day. The squadron unpacked and settled into their new station, excited to be deep in the realms of the renowned 11 Group.

Duty Done: Rusty Leith AM DFC by Cyril Ayris

A History of RAF Drem at War by Malcolm Fife

Young Man - You’ll Never Die by Merton Naydler

Australians at War Film Archive: Colin Leith

www.rustyleith.com

St Peter's old collegians Facebook page

http://www.airhistory.org.uk/

453 Squadron (R.A.A.F) Squadron, 1941-1945, Buffalo, Spitfire by Phil H. Listemann

Personal records: Jim Ferguson

Personal records: Russ Ewins

Personal records: Len Hansell

Personal records: Rusty Leith

Personal records: John Barrien

Personal records: Fred Cowpe

The National Archives, Kew: AIR 28/219, Drem

NAA: A9186, Unit history of number 453 Squadron - June 1942 to January 1946

NAA: A11335, 3/4/AIR, No 453 Squadron - Operations Record Book - F540 and 541 Copies

NAA: A9301, 403917, FERGUSON JAMES HUMPHREY

NAA: A9300, MENZIES A R

NAA: A9300, BLUMER A G B

NAA: A9300, NOSSITER B T

NAA: A9300, CLEMESHA R G

NAA: A9300, RILEY C G

NAA: A9300, REID D J

NAA: A9300, FOWLER D M

NAA: A9301, 416291, DH STEELE

NAA: A9300, RILEY C G

NAA: A9300, DARCEY R J

NAA: A12372, R/6288/H R C FORD

NAA: A9300, MCDERMOTT F R

NAA: A9300, HALCOMBE F K

NAA: A9300, THORNLEY F T

NAA: A9301, 416070, WHITEFORD G

NAA: A9300, PARKER H M

NAA: A9301, 401784, FURLONG J R

NAA: A9300, BARRIEN J

NAA: A9300, RATTEN J R

NAA: A9300, WATERHOUSE J H

NAA: A9300, YARRA J W

NAA: A9300, CRONIN L F M

NAA: A9300, HANSELL L J

NAA: A9300, DE COSIER M H I

NAA: A9300, SWIFT N F

NAA: A9300, EWINS R H S

NAA: A9300, LEITH C R

NAA: A9300, SWIFT T A

NAA: A9300, WHITE W J

NAA: A9300, WALDRON W W

© Michael Ferguson-Kang